A friend in Seattle who happens to be an NHL fan (Lightning) was asking me about “the bubble” playoffs the other day. It took us a few minutes to piece it all together but then I remembered a story I had written back in October about one of the most bizarre experiences in NHL history.

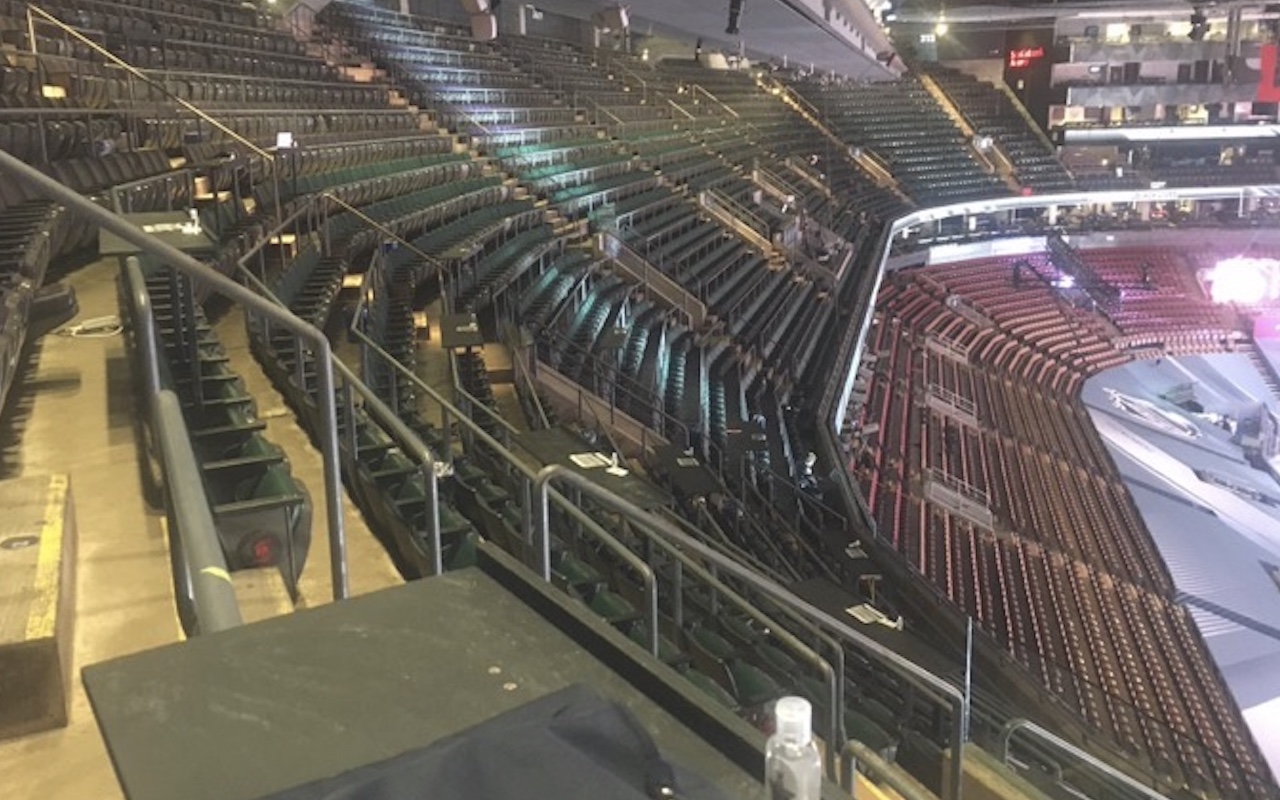

Because of the Covid pandemic in 2020, the Eastern Conference Stanley Cup Playoffs were all played in front of no fans at the Scotiabank Arena in Toronto. The west teams played all of their playoff games in a mostly empty Rogers Place in Edmonton, also the host of both Conference Finals and the Final.

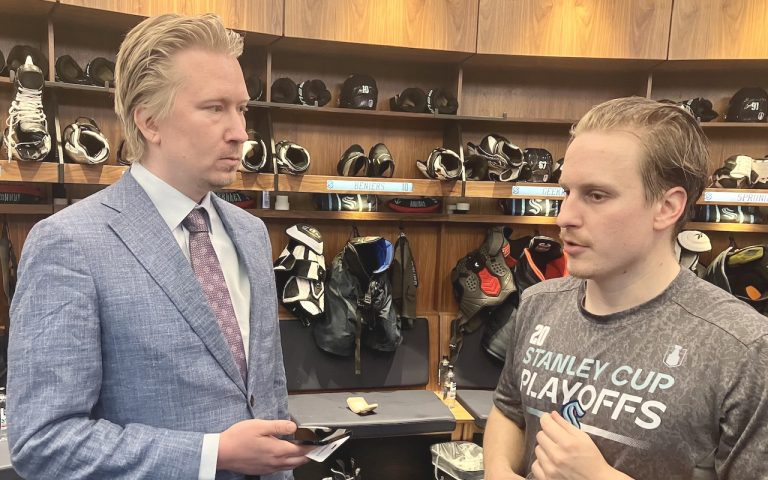

Almost empty meant that team and league personnel, plus a limited number of media were allowed in. I was one of the handful covering the weirdness in Toronto.

There was sort of an elitist element to being an NHL media member attending playoff games the summer of 2020. While almost all radio, TV, and print folks were covering these games from their respective home offices or living rooms, there was usually about 7-to-12 of us watching the games in person.

It was a strange opportunity. If you pro-rated my seat, with 11 other people watching, outside of club and NHL personnel downstairs, based on a conservative average playoff ticket price in Toronto of $400, my chair was worth $621,600.

Silly yes, but the fact is, we were getting a private viewing of something that should have had about 18,700 people in attendance.

There was so much space around me that my little table in section 305 felt like a private office. It was chilly cold without crowd body heat and I’d wear a sweatshirt over my clothes for each game.

Somehow there was also something very comfortable and reassuring about it. It’s a great place to get work done. No distractions, and over the top of my laptop I had an exclusive view of Stanley Cup Playoff games.

A Different NHL Routine

The routine was simple and easy. Entering from Maple Leaf Square, I walked and climbed through a short maze of doors and stairs to the second floor of the Scotiabank Arena. Through the media door I’d be met by the guy or gal who asked me the routine Covid-exposure questions and took my temperature. They put a little paper wristband on me, signifying that yes, once again, I was healthy enough to attend. Then a quick hello through security and a bag check, “hi-how-are-you” to a couple of the NHL PR folks, and into the elevator.

One floor later I walked into what’s normally a bar adjacent to the concourse on the 300-level. I’d walk down that concourse to the curtain that drapes over the entrance to sections 306-305. Through the curtain, I turned and climbed 24 little steps to row 12.

During that walk down the dimmed hallway I’d usually see a maximum of one other person, normally a security guard sitting in a chair looking at their cell phone. Or I’d see someone I’d known for ten or twenty years, but they didn’t recognize me behind my mask and I’m not always sure I recognized them.

My particular viewpoint was probably the best for watching the game. Higher than where NHL scouts would sit, but in the position they like, at an angle where you can see down the boards on both sides and note the action at both ends.

The action was tantalizing in small doses. I documented the “bubble-affect” on the NHL players and on the teams. What drove Bruins starting netminder Tuukka Rask to head home after Game-2 of Round-1 had an influence on many of the players. No family and no fans simply sucked.

Typically the first round is the craziest. Not that year; teams seemed to be checking out mentally. But it did have a very positive side effect for the later rounds. Teams were so committed as it went on, so desperate and pissed off about being in the bubble for about six weeks by the time the Conference Finals started, they played some really intense, hard fought hockey.

But it still wasn’t the same.

Either way, huge props to these guys who fought their way through it. And congratulations to the NHL for pulling it off. Yes, motivated by ad’ revenue and sponsor commitments, it was also a commitment to Lord Stanley’s chalice. With labor peace looming wonderfully for the next half-dozen years, why not do what one could to make a Cup presentation.

I didn’t move on to handle coverage in Edmonton for the Conference Finals and Final.

One cool thing was seeing the 4th longest game in Stanley Cup history. In Game-1 of the first round between the Tampa Bay Lightning and Columbus Blue Jackets, Brayden Point finally scored for the Bolts at 10:27 of the 5th overtime. I had moved down to the rail at the front of the section to watch that period, focusing in on just how damn tired the guys looked.

I think it was mention of this historical game that actually got the conversation with my Lightning fan friend started.

It was quite a match and quite a moment. It forced the postponement to the next day of the game I was really there to cover. I think it was Pittsburgh and Montreal. The Tampa Bay match just turned out to be a very long bonus.

Regardless, outside of being at the first New York Rangers game after 9-11 and constantly fighting back tears with a grapefruit-sized lump in my throat every time a group of cops or firemen walked by on the concourse to an ovation, the bubble was easily the most unusual NHL experience from decades around the game.

I hope to hell we never have to go through it again.